The first and a lone ranger: William Kreutzer

By Joe Gschwendtner; photos courtesy of Sedalia Historic Museum and Gardens

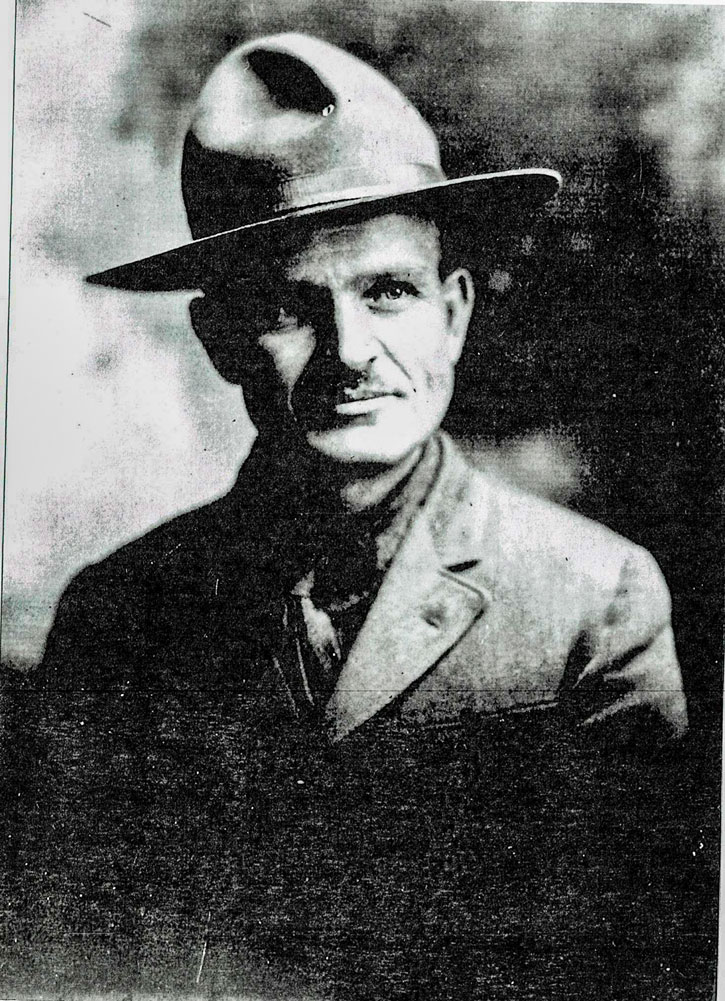

William R. Kreutzer, perhaps 30 years old. “Things were either black or white for the tightly disciplined Kreutzer, never gray…

In 1897, President Grover Cleveland began to protect America’s resources, designating 21 million acres of timberland as National Forest. He appointed Colonel W.S. May as his Colorado and Utah Forestry Superintendent who then immediately advertised the need for rangers. A determined 20-year-old Sedalian, William R. Kreutzer, responded pronto to the newspaper advertisement, riding 30 miles on horseback into Denver.

One might have judged him too young, but he came with serious credentials, including wanting to emulate his grandfather’s profession in Germany. Kreutzer was the complete outdoorsman, raised in a cabin within the Plum Creek Timber Reserve. May sensed something unique about this lad and awarded him a 300,000-acre territory on the spot. With the appointment, Kreutzer became the United States’ first forest ranger.

It was primarily a fear of forest fires that moved May. His instruction to Kreutzer provides the clue. According to records, he ordered Kreutzer to “take horses as far as the Almighty will let you and get control of the forest fire situation….as much as possible. As to what you should do first, well, just get up there as soon as possible and put them out!”

Where forest fires were concerned, Kreutzer’s best move was always persuasion. Like Smokey the Bear, he urged locals to become more sensitive and proactive, as healthy forests were in their own interests as well.

Though weighing less than 170 pounds, Kreutzer was a force to be reckoned with. He had to be. His greatest challenges came from men and women who knew few boundaries. That the government now controlled the open range and forests did not play well among those who had tamed the West. Until rangers like Kreutzer appeared, cowboys and ranchers had been undisputed kings of the West; only their rules applied.

Most were shortsighted, treating the plains and forests like personal property. The worst, called “land skinners,” did what they pleased with timber, using any rangeland needed to graze their cattle. Railroaders and loggers were equally bad; each wanted their fair share of the forest timber. All parties often clashed violently. Beyond town, the West was still chaotic.

Kreutzer’s job was to protect the land with control concepts like land management, selective cutting and use of permits. Often, he settled fights between cattlemen and sheepherders. Unloved by both, bullets could fly. He took to wearing his badge inside his coat.

Kreutzer was a gunslinger and marksman, firing his Colt 45 accurately from both hands. Transferred to Battlement Mesa in 1901, it is said he once was challenged in his cabin by two men with sidearms and given an ultimatum. Angrily, they told him they didn’t want or need rangers on their mesa.

Quick-witted, he offered his right hand to one, ostensibly to shake it. In that same movement he took the man’s revolver with his left hand, fired a volley through the roof with his right, and grabbed the other fellow’s gun before he could react. The conversation that followed turned out to be much more rational.

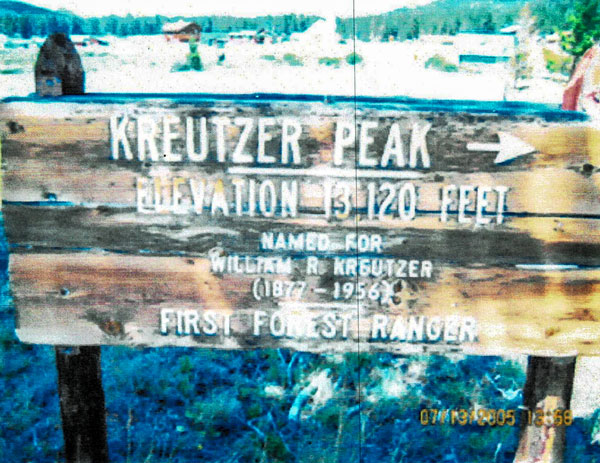

Stories of Kreutzer’s travails and triumphs are legendary, his more than 41 years of service unrivaled. Len Shoemaker wrote a biography, Saga of a Forest Ranger in 1958 detailing Kreutzer’s life. In that same year, a 13,120-foot peak east of Tin Cup, Colorado was named Mt. Kreutzer in the ranger’s honor.