Silas Soule: The good die young

By Joe Gschwendtner; courtesy photos

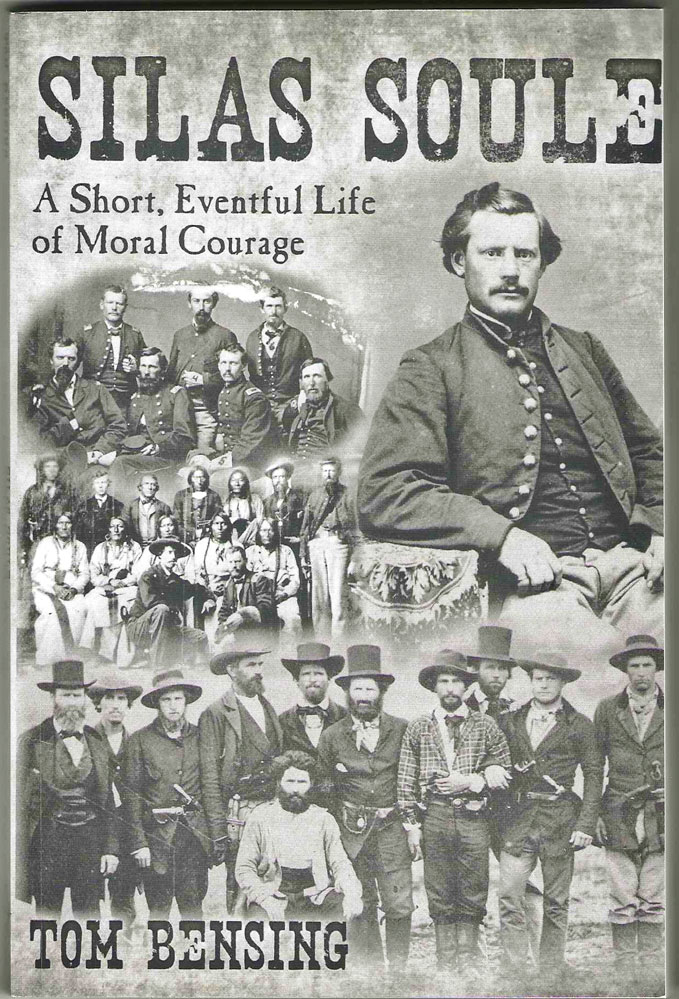

Silas Soule (top right): “Jayhawk, adventure-seeker, and soldier experienced much of what engulfed the nation in his lifetime.” Courtesy Byron Strom and the Ann Hemphill Collection.

In 1859, Sarah Coberly operated a halfway house rest stop in Huntsville, on the stage road to Colorado Springs. Husband James died early of an Indian arrow in Franktown. She had three daughters, Hersa, Mattie and a third, the adopted Lizzie Fields. Hersa first met the gallant Silas Soule as a traveler.

Soule was no ordinary fellow. Of Mayflower lineage, he was born in 1838. Father, Amasa, cooper by trade, was a fervent abolitionist. The family moved near Lawrence, Kansas in 1855, already a battleground of free and slave-staters. Immediately, Amasa became involved in aiding fugitive slaves via the Underground Railroad. Silas joined him eagerly.

By age 21, Silas had masterminded the jailbreak of fellow abolitionist Doctor John Doy. In 1859, he infiltrated the Jefferson County Virginia Jail, offering to help John Brown (of Harper’s Ferry fame) escape before his execution date. Brown refused, preferring martyrdom and warning America that “the crimes (of slavery) would never be purged away but by blood.”

Later, Silas tinkered at gold mining near Denver. Finding nothing, he joined the Union Army. His abolitionism and military connections earned him a lieutenant’s billet in Company K, Colorado First Infantry in 1861.

After training, Soule participated in Glorieta Pass operations against Confederate forces. Later as a Union Army recruiter for Denver, Hersa Coberly was never far away. He also forged a friendship with Rocky Mountain News editor, William Byers. Promoted to captain and cavalry officer in 1864, Soule came under Colonel John Chivington’s command.

As the Civil War raged, Native American rampages were still commonplace, the result of broken treaties and being herded into early versions of concentration camps. Under severe pressure in 1864, Governor John Evans developed his solution, directing all “peaceful” tribes to settle on the Sand Creek Reservation near Ft. Lyons. Simultaneously, he created a temporary militia under Chivington to seek out hostile (non-cooperating) Native Americans and destroy them.

Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle was a begrudging, hopeful pacifist. Trusting Evans, he led his people, some Sioux and Arapaho included, to the sanctuary designated by Major Edward Wynkoop. All went well until Chivington proved ineffective in finding hostiles. Thus, it appears he viewed the unsuspecting Sand Creek campsite as his chance at redemption.

The subsequent ruthless slaughter of unarmed innocents is settled history. Not well known is that Captain Soule and his troop refused to participate, convinced it was a massacre. Later, Soule would testify accordingly.

Silas and Hersa Coberly’s romance heated up again in 1865 when Silas served as Denver’s Provost Marshal. Married on April 1, William Byers himself wrote the announcement.

On April 23 several drunken friends of Chivington, Charles Squier and Williamson Morrow, were shooting up the town. Accounts report Soule confronted Squier head-on, both men drawing weapons simultaneously. Within seconds, three weeks after her marriage, Hersa became a widow.

Mystery still clouds Soule’s death. Was it a contract assassination? He was unpopular, a snitch to many, and a marked man by Chivington. Most still viewed Native Americans negatively.

Even Coberly family sympathy itself was mixed, given the circumstances of James Coberly’s death and brother Joe’s support of Chivington’s Sand Creek actions. What is undisputable was Soule’s moral courage.