McMurdo Gulch Civilian Conservation Corps

By Joe Gschwendtner; courtesy photos

Photo taken in 1937 and made available through Google Earth. Today, Castle Oaks Drive runs between the barracks and the vast athletic field including a baseball diamond on right.

The stock market crashed on Black Friday in October 1929, ending the Roaring ‘20s. That day marked the beginning of the greatest economic downturn these United States have ever known.

President Franklin Roosevelt sought ways for the federal government to stimulate the economy. One program was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Given life through Congressional legislation, it was a voluntary public works relief program for unemployed and unmarried men. By 1935, the program had trained 500,000 young men and put them to work. Their mission: to preserve the nation’s depleted resources.

Known antiseptically as Camp SCS-7-C and like all others, Castle Rock’s camp was run by a handful of military officers with men recruited elsewhere. Our young men hailed from the Providence, Rhode Island area and their unit was designated Company 1845.

The site chosen was on McMurdo Gulch at an elevation of 6,336 feet, just south of the original homestead claim of Scotsman George McMurdo. When recruits first arrived in July of 1934, they numbered 195 and were housed in 30 pyramidal tents with dirt floors.

Five barracks would soon be built, each housing 40 men. An 800-foot well was drilled and by September, the camp had running water and electric lights. Records show that there were eight company commanders, seven doctors, four educational consultants and three project superintendents over the life of the camp.

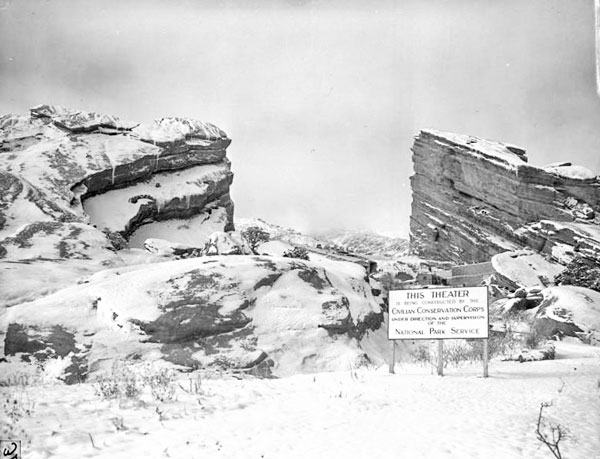

Red Rocks Amphitheater in winter under construction. Note the CCC sign in the right foreground. (Photo courtesy of Library of Congress.)

By today’s standards, the young men’s accommodations were bare bones. Yet, since most came from poverty-stricken homes, it was an improvement. The meals were robust and clothing was adequate. Some of the supplies were from a World War I surplus.

Each corpsman was paid $30 monthly and was required to send $22 of it home. Unlike the army, free time was not policed in any way. However, these were the times of Sheriff Charles (Bert) Lowell. Early on, when a group descended on Castle Rock to paint the town red, Sheriff Lowell confronted one of the biggest partiers by dropping his pistol belt. He then dared them individually, proceeding to whip each fellow as he came forward until his message was clearly grasped. It was his town, not theirs.

Men labored five days a week, six hours a day. Training consisted of elementary, high school and college level courses as well as eight vocational paths. All were required to participate in on-the-job learning under the auspices of the Soil Conservation Service. Crews worked primarily on water erosion and soil-saving projects. Assignments ran the gamut: building levies, dikes, diversion ditches, contours and terraces, rip-rapping, conduits, pipelines, quarrying, seeding experimental farm plots, rodent control, tree planting and grass seeding.

As government programs go, the CCC was likely its most successful ever. Not only was it run with military precision, it left most members with an indelible impact on their moral code, far better educated, with marketable skills and a vastly improved pride of person.

Emblematic of the quality of the CCC’s work is Red Rocks Amphitheater, built jointly with CCC manpower from Camp Morrison (SP-13-6) and the Works Progress Administration. As World War II loomed, CCC enrollees became high priority resources and the program ended in 1942.