Love in the White House

Love works at his easel in Jarre Canyon (photo courtesy of the Love Family Collection).

Last year, we featured Sedalia’s Dr. Minnie Love. She was a gifted, charitable woman and suffragette. But for some ill-advised pursuits in antisemitism, Love would have attained unadulterated fame.

Her son, C. Waldo Love, noted another of her impolitic acts. She said of him that “[If he] didn’t have enough brains to get through school, he would have to become an artist, which apparently requires no brains.”

Turns out, she made another mistake. Likely one of Colorado’s most famous artists, Waldo proved her very wrong.

Born in 1881 in Washington D.C., Love bounced around early on: San Francisco, New York City and to Denver in 1893 after the family lost all in that year’s financial panic. His father found work in Denver but homesteaded in Sedalia’s Jarre Canyon in a 16- x 20-foot cabin.

Waldo was schooled in Denver, failing to graduate from East High School. At this juncture, with his mother’s thinking, he found his way to the Student’s School of Art, ran by Henry Read. Read gambled big on Waldo’s un-blossomed talents and offered an 18-month apprentice-student package.

Waldo’s big break came when a drawing of a male nude earned him a two-year scholarship to The Art Students League of New York. A bout with pneumonia returned him to Denver, where he produced several seminal works, which were featured at the Denver Artists Club.

On return to New York, Waldo completed his courses, then moved to Paris for a year. Frustrated, he returned to Denver in 1905 and picked up decent commissions as a commercial artist. By then, he had taken a liking to his father’s Jarre Canyon cabin, briefly acting more like a cowboy than artist.

Waldo returned to New York in 1906. He reunited with former girlfriend Orilla Riley and the couple married in 1908. She was almost certainly his missing piece.

Waldo’s rise thereafter became meteoric. Though moving back and forth between Chicago and New York, his commissions grew, and works for major companies appeared in Ladies Home Journal and The Saturday Evening Post. His business successes became integrated with developing talents in the fine arts, especially oil on canvas. His reputation continued to soar.

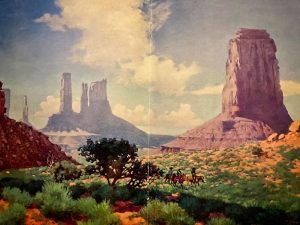

“Monument Valley” oil on canvas, 1945. Reprinted with the permission of the Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway.

Two decades later, he, Orilla and their family of three children returned to Denver. Nationally recognized, his best portraits seemed to stem from his western immersion, especially the Jarre Canyon cowboy year. This was evidenced by his work “Antelope Hunt.” Among equally brilliant works were portraits of Jim Baker, Baby Doe, and panoramas depicting nature scenes of Douglas County and Colorado. “A Still Life with Columbines” in 1909 may well be one of his very best.

Showing extraordinary versatility, Waldo produced a remarkable piece of the Monument Valley Park, absent the common red colors dominating the landscape. Not long after, the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway purchased it from him to use it on the railway’s first class dining car menu.

So it happened that President Ronald Reagan, fan of western life and culture and an actor in “Death Valley Days,” also admired Waldo’s work. By personal request, the Monument Valley painting was loaned to be shown in the White House. Later, it was featured at the opening of the William J. Clinton Library and Museum. Small wonder that C. Waldo Love’s work stands tall in these parts today.

By Joe Gschwendtner; courtesy photos