Douglas County’s first immigrants

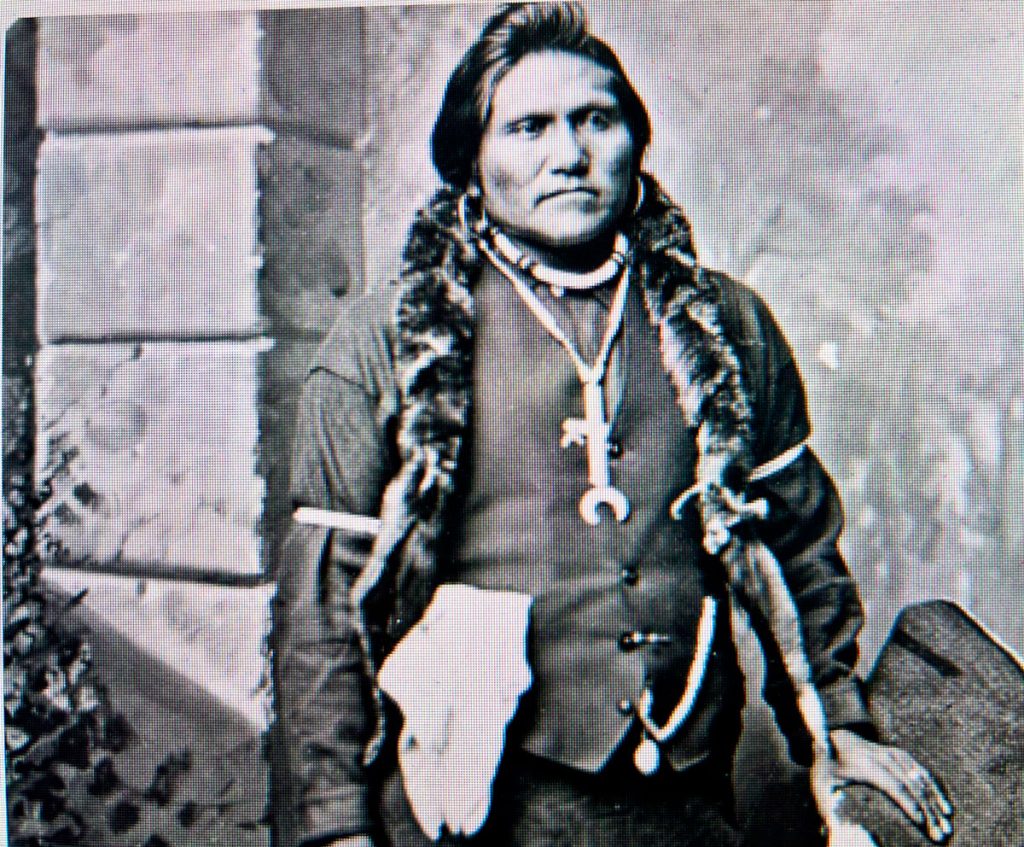

A Southern Ute Native American, circa 1880, courtesy of David Rich Lewis and Utah History Encyclopedia.

The Douglas County Wildcat Lore pioneering stories would be incomplete without addressing the forerunners: Native Americans. In fact, using historian Larry Schlupp’s words, they were indeed our “first immigrants.”

As early as 1500, the Southern Utes found the Douglas County plains and foothills most hospitable, well before any other groups. Tribal history claims Utes were here since “the beginning of time.”

The Utes used seasons to their advantage, with men hunting from spring into late fall and the women snaring smaller animals and gathering berries and fruit during that time. Wild onion, dandelion and rice grass were also common to the area and highly valued. Medicinal plants garnered special attention and attempts to grow and cultivate them were early vestiges of Ute agriculture.

Wintering customs found Utes shifting their camps from high foothill locations to designated lowlands with much emphasis placed on wood gathering for the winter months. Among the many individual tribes spread over the southwest, the Utes were the most forceful, especially so after their connections with exploring Spaniards in the 1600s. Horses acquired in trade supplemented the tribe’s legendary mobility and muscle, which made them an even more formidable power.

Three hundred years later, huge Arapaho and Cheyenne bands migrated from their northeastern environs, the Great Lakes area and Canada. Their motivation: the pioneers push westward. Unlike the Utes, neither tribe proceeded beyond the Continental Divide.

As a culture and having come from breadbasket regions like the Red River Valley in the east, the Arapaho had an agricultural bent as well as eight different, secret warrior societies.

Unlike the Arapaho, the Cheyenne tribe’s westward drift was more a function of their arch enemy, the Dakota Sioux, pushing them to this region.

In the beginning, the Cheyenne gravitated to the lowlands of the Arkansas and Platte Rivers. In the first Treaty of Fort Laramie in 1851, there were apparently enough regional and cultural differences that the Northern and Southern tribes were recognized as separate tribes. Periodically, both would meet peacefully as they traded at Bent’s Fort in southeastern Colorado. (Today, Bent’s Old Fort National Historical Site).

In their new territory, the Cheyenne seemed never at peace. They warred with neighboring Kiowas until 1840 and also with the U.S. Cavalry. Later, the Northern Cheyenne with the Arapaho (and the Lakota tribe led by the legendary Crazy Horse) tipped the scales when they battled and bested General George Custer at the Battle of Little Bighorn in 1876.

It was generally understood that in these “Plains Wars,” there was conflict to control the Great Plains between the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains.

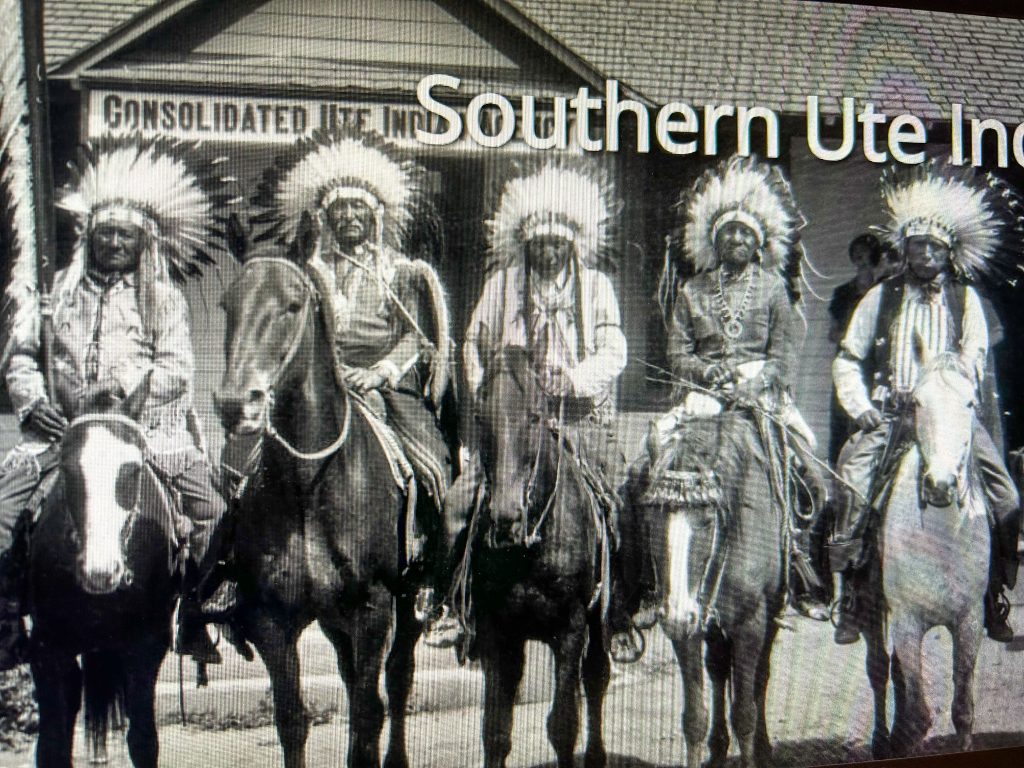

Southern Utes, circa 1880, courtesy of the Denver Public Library.

By Joe Gschwendtner; courtesy photos