Charlie Alexander – of mice and men

By Joe Gschwendtner; photo courtesy of Sedalia Firehouse Museum

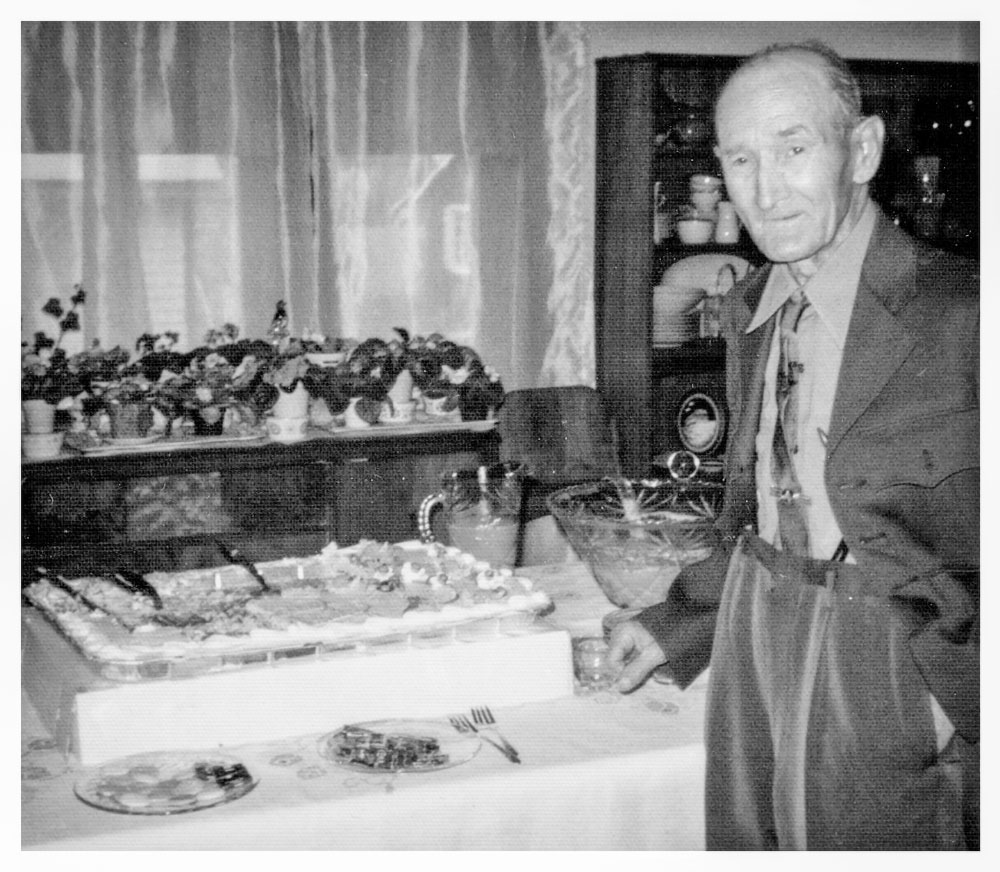

A grateful man on his 90th birthday, Charlie Alexander enjoys his first official birthday cake.

Charlie Alexander was one of Sedalia’s more colorful locals, born a Hoosier in 1882.

His early years were filled with hardship, and he was placed on an orphan train by his mother when he was 11 years old. He was one of 250,000 such children shipped to rural areas of the U.S. from 1854 to 1929. Many of Charlie’s fellow travelers were either orphans, abandoned or homeless, or like him, dispatched by destitute parents in a bitter act of love – giving him better odds to prosper in life than they could have provided.

The orphan train would often stop in agricultural towns, and the children aboard would front themselves in a line at the station. Committees of local citizens generally had done advance, pre-screening work on potential receiving families who might either adopt or at least employ them temporarily. The farmers in turn could select a child or two to join their family or use them as unskilled laborers. The wages were food, lodging and the prospect of a new life.

The bulk of those who selected kids were decent, appreciating the extra help the children could provide around the farm. Charlie was not that lucky and was claimed by a man who was anything but kind. This caused Charlie to become a runaway at 14, and the event was the impetus for his early days of west coast wandering.

First, he hitchhiked to California. Then he moved on to Alaska for five years finding himself right in the early days of the state’s gold rush. Still rootless and merely subsisting, he worked his way down the west coast through Washington, Oregon and back to California again. By 1941, he had relocated eastward where he registered for the draft in Sanford, Colorado.

It was our Sedalia that finally captured his fancy, and where he made a meager living doing carpentry work and odd jobs. Uneducated and fiercely independent, he was unusually observant and as engaged as he needed to be to push on with his life.

Charlie was anything but a gourmet. In fact, he was wild about Dinty Moore Beef Stew in a can, which he ate for most every meal. As a cook, he could make a mean venison jerky and an unusual Trinidadian bread, made from hops.

Adamant and unyielding at times, once while hospitalized, he refused the food served him there. So stubborn in fact, his recovery became stalled due to his refusal to eat. It wasn’t until close friends brought him his comfort food that the recovery began again.

Charlie was not just eccentric about food, but entertainment as well. He was known to sit on the floor of his very small cabin and shoot mice as they ran across his floor.

In his entire life, he had never celebrated a birthday with a cake. Local neighbors Art and Mabel Beeman changed that when they surprised him with a cake with 90 lit candles in 1972.

Not surprisingly, Charlie died as he lived, inconspicuously in 1974. His remains rest among other dynamic Douglas County pioneers in the Bear Canon Cemetery at the foot of Wolfensberger Road.