Castle Rock: aptly named

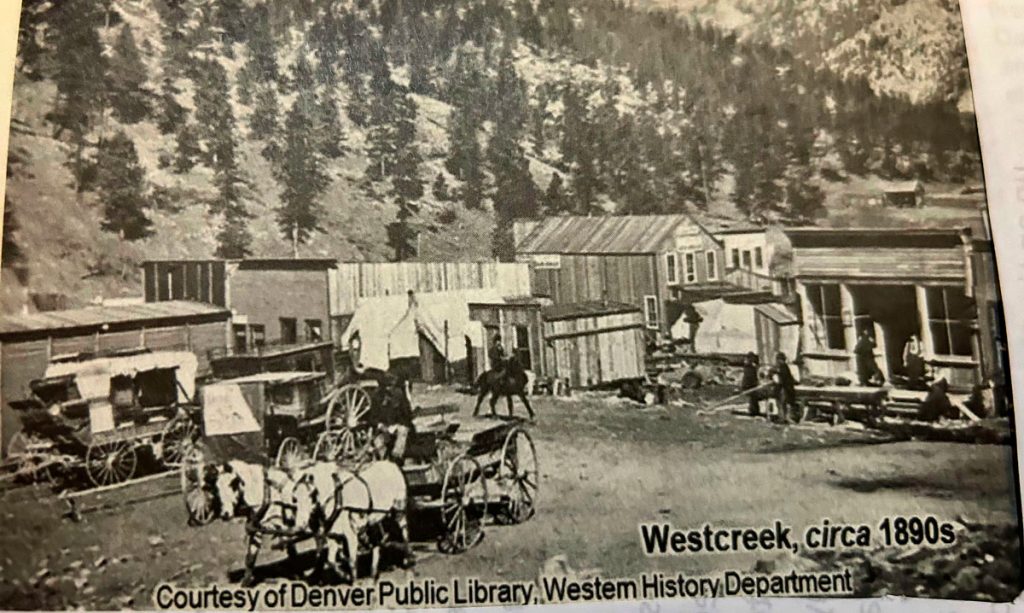

Westcreek in the 1890s.

Castle Rock was named after the rock formation towering over it. An outlier for its name, it is also the perfect icon for minerals that were early foundations for Douglas County’s population growth. Our tidal wave of humanity today all started with a bit of greed.

Parallelling California, the first hint of gold in these parts was tempting. Our 59ers were motivated by stories from the Russellville-Franktown area. A goldrush it was, but especially short-lived by any standard. Perhaps almost symbolically, some early extraction efforts now remain buried beneath Reuter-Hess Reservoir waters. And indeed, water is “gold,” the key to the county’s sustained growth in the future.

Much later, in 1886, William Wanner, discovered gold near Dakan Mountain, southwest of Castle Rock and near Perry Park. Virtually overnight, a town of eight buildings (saloon included) grew up on the fringe. Its population topped 300 residents until the gold discovery find was determined to be highly localized.

Lastly, on the county’s southwest borders, George F. Tyler uncovered seemingly exploitable quantities of gold on his ranch. The Russellville and Dakan phenomenon was quickly replicated, and the town of Tyler evolved. Later it was renamed Bunker Hill and finally, Westcreek. Meaningful deposits kept speculators there into the 20th century, but the source ultimately played out.

Coal, on the other hand, was a big moneymaker of the day. Near the surface and easily mined, it was in great demand by blacksmiths and forges to produce tools and later, the structural steel necessary for industry. It was most significant as a home fuel. Part of the South Platte Field, four miles west of Sedalia, the Lehigh Coal Bank yielded 100 tons daily. By many, it was seen as the “choicest coal field in the state.”

It too had its run: witness the town of Lehigh, if you can find it. Exploited over several decades, its last vestige was a small sign acknowledging its once thriving existence.

The quarrying industry had better staying power when compared to brethren mineral industries. From 1872 to the early 1900s, feldspar/rhyolite took center stage, immensely aided in its transportation by two railroads that coursed through the county. That railroad spurs were engineered to the base of each major quarry is testimony to the profit opportunity afforded the railroad barons of the day.

The 1881 Madge Quarry (today’s Rhyolite Park) was the first major prolific producer, followed by the O’Brien operation in Sellars Gulch in 1882. Late to the rhyolite party were the short-lived Santa Fe Quarry, dominating today’s Meadows neighborhood. The Plateau Quarry was nearby, the butte above and east of I-25 above today’s BridgeWater development.

At the end of an era, records documented that some 30,000 railcars of Rhyolite had been sent to points west or east via railroad. Its selling point had always been the ease with which masons could shape it to their needs. But with the discovery and development of Portland concrete, which shape could be dictated by its liquid form, Douglas County would no longer be living on the rocks.

Subsequent economic growth in the new century remained sleepy and measured, until the quality of life became the new mother lode. That vein seems endless, at least for the moment.

By Joe Gschwendtner; image courtesy of Denver Public Library, Western History Department