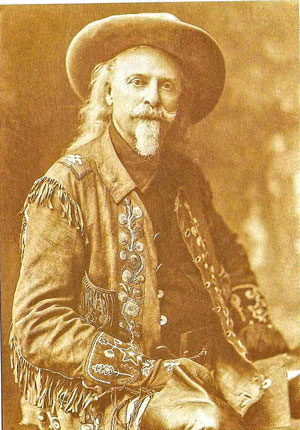

William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody

An American original

By Joe Gschwendtner; courtesy photos

An unsullied hero is rare in these times. Unusual too, is a person who defined an era and culture simultaneously. William F. Cody was an egalitarian when civil rights were ignored or violated in a rush to settle new frontiers. If, as parents today, we seek antidotes to the characters dominating our culture, Buffalo Bill and his code are refreshing, a century after his death.

Born in Iowa in 1846, young Bill’s early history was a westward trail. At age 11, he left home to herd cattle. Later, he drove wagon trains, mined gold, trapped animals for their pelts and joined the Pony Express. At 19, he was already an outlier, having crisscrossed the Great Plains multiple times.

Recognized as a resource, the U.S. Army retained him as a scout in 1865. Beyond navigation, Cody was a peacemaker, respecting Native American tribes and customs. He invariably had or would earn the trust of Native Americans, rightly suspicious of the land encroachments perpetrated by the U.S. government.

Renowned also as a hunter, the Kansas Pacific Railroad contracted him to provide its laborers with buffalo (bison) meat. Records from 1867-1868 indicate he provided 4,282 carcasses – hence his nickname. By 1869, his exploits were on nearly every westerner’s tongue.

William F. Cody and his wife of 51 years, Louise Frederici Cody, are buried side-by-side in Lookout Mountain Park in Golden, Colorado.

Author and dime novelist Ned Buntline of the New York Weekly wrote a story about him, long on aggrandizement. A serialized novel, Buffalo Bill, King of the Bordermen quickly followed and a snowballing legend was kicked into overdrive. Fact-checkers were in short supply in those days.

Cody’s second career was showman, beginning spasmodically at age 26. After a brief, mediocre stint as a stage actor, he organized a troupe, a traveling show called the “Buffalo Bill Combination” including “Wild Bill” Hickok. These were learning years. Though well-received, Cody hit stride with his circus-like extravaganza, “Buffalo Bill’s Wild West” show. It was and remained a spectacle of the West, its popularity never to fade. Today, some regard it as the beginning of the modern rodeo.

Using equestrians from the world over (Turks, Gauchos, Arabs, Mongols and Cossacks) in an opening parade, everything else followed. Including star-studded casts of Native Americans, notables like Annie Oakley and other historical western stars. There were main events of skill, racing, shooting and other rodeo-type sideshows. This included wild west shootouts, stagecoach robberies and Pony Express rides.

Cody rode a showman’s wave for 40 years, including a presentation to the Queen of England, the Pope and other wildly successful European tours. He paid performers well, women and Native Americans the same as white men. He was also an early champion of women’s rights and universal suffrage. Free passes were reserved for orphan children in each town he played. Larry McMurtry (best-selling Western author) called him “the most recognizable celebrity on Earth.”

Alas, by 1913 his finances and management had slowly eroded. Money owed to Harry Tammen (The Denver Post co-owner) resulted in a seizure of Cody’s assets and their transfer to the Sells-Floto Circus. William Cody died in Denver in 1917, and he is buried on Lookout Mountain in Golden. Roughly 20,000 people embraced his memory at the funeral, and more than 400,000 people visit his gravesite each year.

Should this story strike a chord in you, visit the Buffalo Bill Museum, adjoining Buffalo Bill’s grave. It is a compelling curation of his life.