A virtuoso in the Valley

From the choruses of New York City theater to teaching students the art of musical performance, Bob Harrison has had an interesting career.

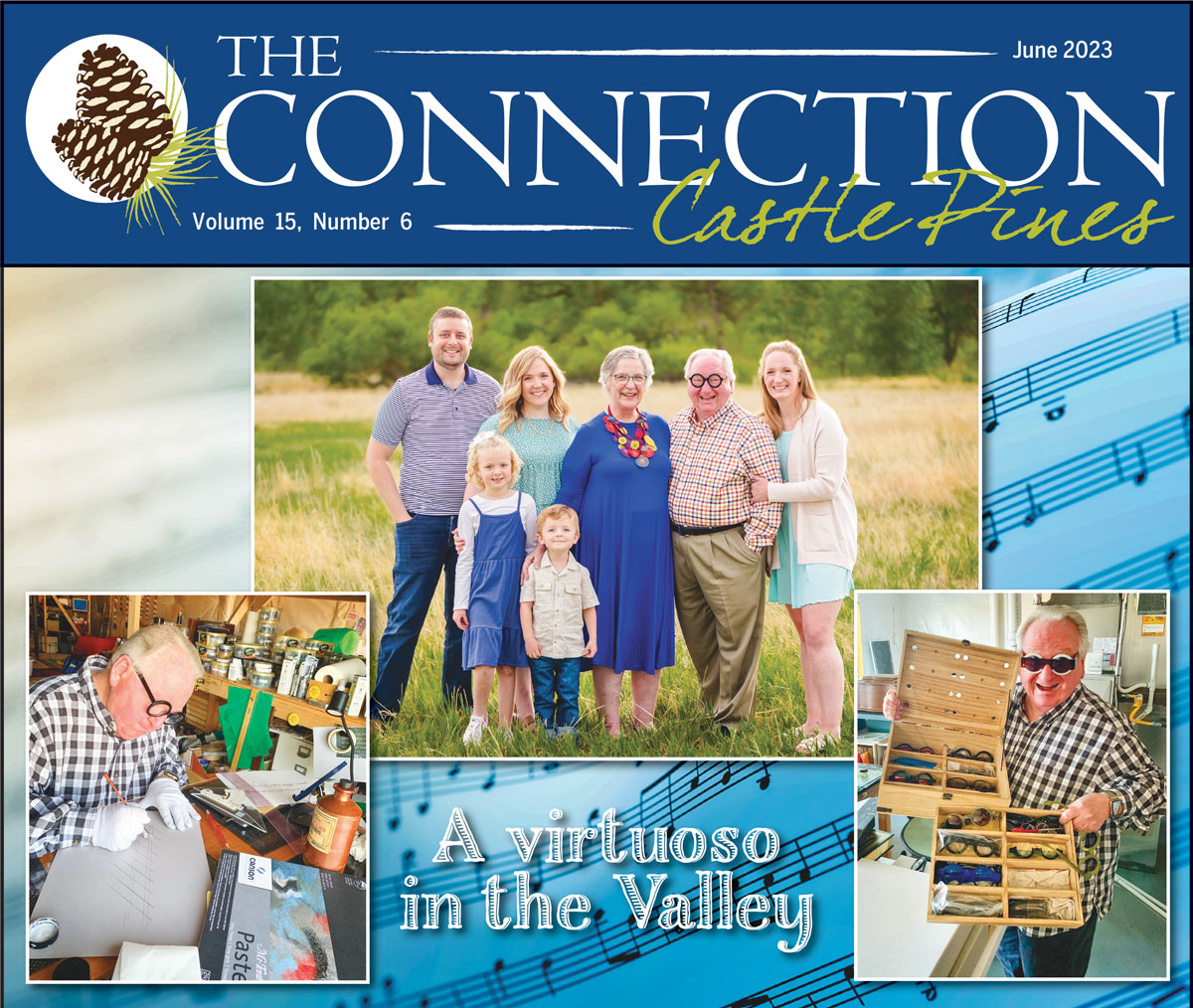

Today, the retired virtuoso lives with his wife in Castle Valley with his two dogs and a parakeet. He is a master penman – someone who has mastered the art of calligraphy and penmanship – and a collector, and to see him out and about, look for a gentleman with eclectic, statement-making eye glasses (one of his collections).

Harrison’s journey began in the Midwest.

Born in Dodgeville, Wisconsin in 1949, Harrison grew up in a modest home. He knew he wanted to pursue music and in high school was invited as a guest chorister to perform for President Nixon at the White House. He attended Milton College majoring in voice performance, and there he met his wife, Sandy, also a music major.

“Even then, it was a risky degree,” Harrison said. “But I wanted to be a performer. Sandy played piano for all my voice lessons, and when I did my senior recital, she accompanied that.”

After graduation in 1971, he proposed to Sandy – who had another year left at Milton – and moved to New York City.

Harrison pursued auditions and landed roles in the choirs of churches and synagogues and said the money was good. He eventually sang for a big chorale agency, getting jobs with the American Symphony, New York Philharmonic, and the Gregg Smith Singers.

“There was a lot of work,” remembered Harrison. “I had no trouble getting gigs, but it was rushed and hectic with rehearsals during the day and a concert that same night.”

Sandy finished her last year of school, and the two married in Wisconsin. After a short honeymoon, they settled in Harrison’s studio apartment in Manhattan. Sandy found a job teaching music at an elementary school.

By 1976, work for professional choristers began to wane because of the financial crisis in New York, so the couple looked for a change. Harrison wanted a master’s degree in voice performance with a particular professor at the University of Wisconsin, so off they went to Madison. His professor recommended that Harrison pursue teaching music; and he did.

After completing his master’s degree, the couple bounced around to a few one-year sabbatical replacements: University of Wisconsin – Oshkosh, Wichita State University and then to the University of Arkansas.

“I worked one-on-one with students so that they could perform with a sense of accomplishment and so that they could be capable of communicating words and music to an audience,” said Harrison. “As performers, we owe it to you to leave the concert hall with something you didn’t come in with.”

The couple eventually grew weary of moving so often, and Harrison began looking for a tenured position.

Luckily, the University of Colorado Boulder was looking for an assistant professor in music. Harrison came out for the interview and saw the Rocky Mountains and the deep blue skies for the first time and crossed his fingers. He took the job, and the couple moved and eventually welcomed two daughters in Boulder.

As retirement age approached, Harrison applied for a position at the revered music school at the University of Indiana, a place he had wanted to attend when he graduated from high school but knew he needed more musical experience. He got the position and finished his career at the highest level.

In 2015, the Harrisons retired to a condo in downtown Denver, and when grandkids came, they moved to Castle Pines to be closer to family.

One of Harrison’s hobbies and passions is scripting. He studied the art under William Lilly, the last graduate of the Zanerian College of Penmanship, and Harrison worked until he achieved the gold seal, making him a master penman.

To be a master penman takes patience. The ink, the paper, the tools, the flourishes have to be precisely right or it is considered unacceptable.

“There aren’t many of us who are masters,” said Harrison. “When done correctly, I should be able to create a perfect, elliptical oval for every letter scripted,” he proclaimed. From the time he sat at his desk, turned on the ink and water stirrers and put ink in the pen, it took two minutes for him to create two precise letters, each 3/16th of an inch, the required measurement.

When Harrison isn’t scripting in his basement studio or spoiling his grandchildren, he listens to music on his Regina Music Box, circa 1919, “the music box of music boxes with a priceless sound,” he said. He also owns a gramophone with a 24-inch horn, has a fountain pen and pen holder collection, and of course, dozens upon dozens of eye glasses he has collected from everywhere over the years.

In high school, Harrison (first row on the far left) was selected to be a guest chorister at the White House to perform for President Nixon (center).

Article and photos by Hollen Wheeler; photos courtesy of Bob Harrison